Writing software is an act that, ostensibly, anyone can perform. You sit down, turn on a computer, open an IDE, an editor, VI if you have a pure heart, or anything else (yes, Notepad counts too), and start typing.

You don’t even need detailed specifications: what are they for when you have everything in your head? Sometimes all it takes is an idea and the will to achieve a result. And something, inevitably, happens.

The first “Hello World” is always a magical moment, but it’s just the beginning.

Once the first hurdle is overcome, one discovers that writing software is a continuous process of learning and adaptation. Even if it’s complicated at first, over time you learn the rudiments: frameworks, libraries, design patterns. You understand how to structure code, how to modularize it, how to test it. And in the end, after days or weeks of work, you get something that works—maybe not exactly as we had in mind, but it works: and in that moment, it’s an explosion of adrenaline and satisfaction.

Even the most pessimistic, those who struggle to even ask their mother for a glass of water, find a solution after hours, days, and weeks.

Once there were friends, then came forums. Today we can even rely on artificial intelligence or an agent: we write our idea, even ungrammatically, and the magic begins.

But today I don’t want to talk about this. Let’s leave aside for once the romantic aspect of programming, the popular belief that it’s enough to put your hands on a keyboard to do incredible things, and let’s not talk about how software is built or how a result is reached—the world is full of courses and manuals.

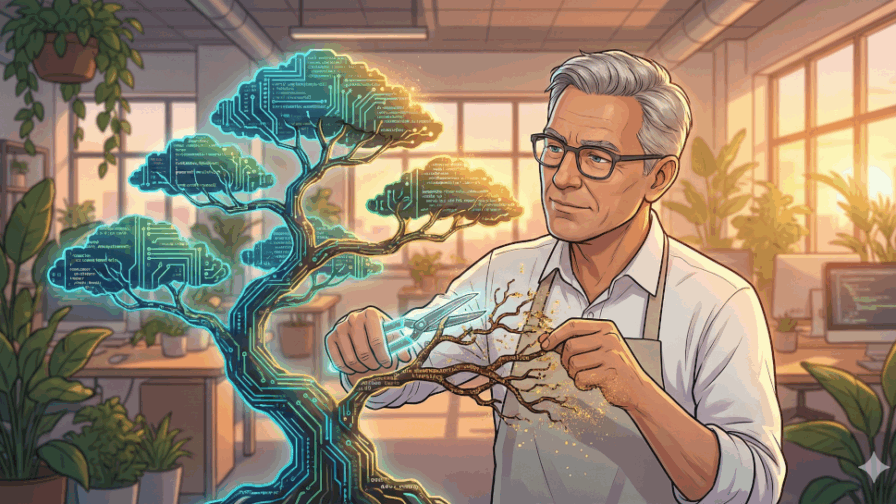

What I would like to talk about today is one of the most complex and least discussed aspects of programming: the courage to remove code.

The Real Challenge Is Not a Working Program

The result is only the first step in building software. Any programmer, more or less convinced of their means, will always say they can do it. Maybe they’ll lie a little about the timing or the real goals, but their answer will always be: “I can do it.” (I exclude from this group the chronic pessimists who start by saying “it’s impossible”; we’ll discard them for practicality).

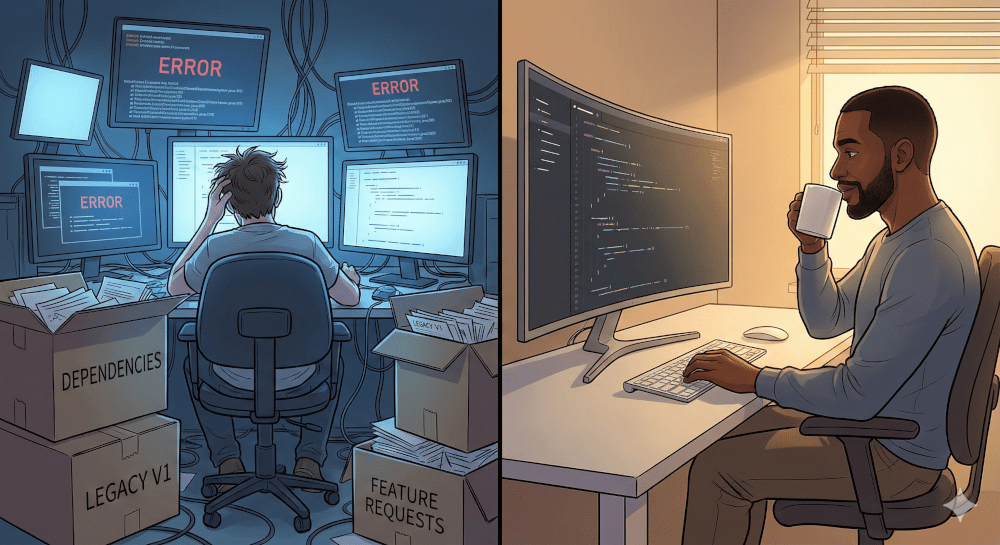

The real challenge is therefore not delivering a working program. The real challenge is not getting overwhelmed by one’s own software: not losing control of it, not turning a trivial 10-line REST service into a disk-eating monster (and I speak from personal experience).

Software growth is entropy and the expert programmer's job is to fight this entropy.Often code is compared to an asset, when in reality it is a liability. If we reason thinking that the code we write is an asset, we lose the most fundamental aspect of the whole creation process: when we write code we are creating a debt. Every line of code must be read, understood, maintained, tested, and, one day, updated or removed.

The less code there is, the smaller the attack surface for bugs and the lower the maintenance cost.

This is often underestimated, especially in corporate contexts where the focus is on “delivering features” rather than on “maintaining healthy and manageable code”.

Those who work for enlightened product companies should know how important maintenance, removal of obsolete code, and dependency management are. Because software is never “finished”. It is a living organism that evolves, grows, sometimes gets sick. When this vision is missing, there is a lack of planning that sooner or later will inevitably lead to collapse.

I have had the fortune/misfortune to follow both types of projects. Some where there was only one goal: deliver, and which over time imploded into tons of uncoordinated code; others where it was normal to do continuous refactoring, remove obsolete code, and maintain a clean and maintainable code base. The difference between the two worlds is abysmal.

We Are All Serial Hoarders

Do you know the show “Hoarders”? People who accumulate useless objects, filling their houses until they become unlivable. Software suffers from the same pathology.

Whether we write it or, worse, an AI does, the code starts to increase in volume. First a few classes, a few functions, and a few scripts, but over time we find ourselves flooded not only with our own code, but also with external dependencies, libraries, modules, plugins. I admit that I too have ended up in this vortex several times, since I insist that every repository I create is self-contained, with all the necessary dependencies to function—I’ve seen projects stall due to the lack of a single library.

The VibeCoders who will read this might not understand me yet, but over time they will realize that AIs have only one goal: to produce working code and, if it isn’t, to convince themselves that it is.

The ultimate goal of an AI is to optimize code or reduce its complexity: this aspect is not important to them and is, for now, completely delegated to us humans. If “humans” don’t worry about the problem, least of all will AIs worry about it for us.

This is where our role changes radically. Generative AIs are powerful “addition factories”, capable of writing thousands of lines in a few seconds. This shifts the human role from “writer” to “editor” or “curator”. Our most important skill will become the ability to validate, simplify, and reject AI-generated code, not just produce it. That is why it is important to guide vibe-based tools: it is not enough to say “generate a CRM”, we must have the architecture, dependencies, future maintenance in mind and consequently break everything down giving one bite at a time to the AI.

If you want to realize if you are on the edge of the cliff or in free fall, try this: inspect the node_modules folder of one of your projects, or those created by Maven or NuGet. In a fairly simple project of mine, I have 1 MB of my own code and 20 MB of node_modules. The feeling that it got out of hand is very high and I am just at the beginning of the project.

Have you ever wondered: “Why does my three-line ‘Hello World’ require 200 MB of dependencies?”? If you haven’t, do it. You will discover a new world, often underestimated, that can turn a simple project into a maintenance nightmare.

Chatting with other programmers, I often hear phrases like this:

I didn't switch from Vue 2 to Vue 3 because I have 18 dependencies that I can't update without rewriting half the project.Code language: JavaScript (javascript)It seems like an excuse, but it’s a reality that many developers face daily.

Dependencies are often taken lightly: we accumulate a mountain of features without a real reason. We add, add, and then add again. It’s easy to add a feature, especially if the request comes from a client or a product manager. But rarely do we stop to ask: “Is this feature really necessary?” and above all, we never go back.

This phenomenon has a name: feature creep.

Feature Creep: The Silent Enemy

The question we must ask ourselves every day, when we see a line of code standing still for years, is: “Is it really necessary?”

The answer is often “no”. But acting on that “no” is costly. Explaining it to a client or a product manager requires a solid technical and verbal justification, which few have the courage, or the strength, to sustain.

“Feature creep” is not just a code problem, but a product one. A user interface with too many buttons, options, and configurations suffers from the same problem. The courage to “remove” also applies to the Product Manager who says “no” to a new feature to keep the product focused and simple.

Also, be wary of those who tell you:

The problem is your fat client, not the dependencies you use.Code language: PHP (php)This is just a way to divert attention from the real problem: the uncontrolled accumulation of code and dependencies. It’s not that one architecture has an advantage over another—the problem of serial accumulation remains the same.

Being really picky, a fat client could have advantages over a thin client sectioned into N services, given that it represents a single point of control, compared to verifying services that are, virtually, used by an uncontrolled number of clients—but that’s another story.

Superfluous features and out-of-control dependencies complicate everything. Software becomes fragile, slow, difficult to maintain. Technical debt grows invisibly, until it becomes impossible to ignore.

The Nightmare of Maintenance

As long as we are “focused on the project” and work daily on features and refactoring, we have some additional probability of managing the chaos. But inevitably, if that project is put aside and resumed after months, or if the team changes a lot, the inevitable drift is chaos and the increase of technical debt.

The higher the number of imported dependencies, the greater the problem of cross-cutting obsolescence.

But with “dependencies” we don’t just think of library X or Y that we use to parse a JSON file. Let’s think of the whole ecosystem: language versions, libraries, frameworks, toolchains, build systems, execution environments, and so on.

Sometimes you end up in a technical cul-de-sac: the update we need conflicts with another fundamental library, which hasn’t been updated yet or whose maintainer has vanished into thin air. It matters little if it is open source—this too is an overestimated concept in software development.

At that point, the choices are few: rewrite parts of the software, accept the security hole, or leave everything as it is, hoping it doesn’t collapse.

It’s easy to say “my software is perfect”. It might be true for the lines you wrote—even if they are often just biases—but it is not for the ecosystem of external components it rests on.

Why Don’t We Remove?

But why don’t we remove? Because we are afraid. Afraid of breaking something (“What if this code was needed for that case X that I haven’t tested?”).

To remove with courage, two fundamental things are needed: technical and psychological safety, but above all the will to do it.

A corporate culture that rewards subtraction is also needed.

In many companies, productivity is measured in “features delivered” or “tickets closed”. But how many times is a programmer praised for removing 1000 lines of obsolete code? A “Pull Request” with -1000 lines should be celebrated. We need a culture that sees refactoring and cleaning not as “chores”, but as an integral and noble part of the development process.

The Courage to Remove

The real programmers are those capable of reducing.

Ken Thompson, co-creator of Unix and the C language, once said:

One of my most productive days was throwing away 1000 lines of code.I don’t know how true this statement is, but the concept is powerful. True mastery lies not in adding, but in knowing how to remove without losing functionality.

There is also a famous quote by Tony Hoare, the inventor of Quicksort:

There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies, and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies. The first method is far more difficult.How can you blame him? After all, his degree in classics, prior to his computer science career, perhaps gave him an edge in understanding the elegance of simplicity.

But since there are no roses without thorns, in addition to this gem, Hoare also left us one of the greatest tragedies of modern computing: the concept of “NULL POINTER”. If it ever ruined your day, now you know who to thank.

Only the Brave Remove Stuff

But back to us. How do we, concretely, remove?

The first step is to remove useless code. It seems easy, but this is where resistances, both structural and human, trigger. To win this battle, adequate weapons are needed:

- Robust automated tests: a test suite that gives confidence that, if something essential is removed, a test will fail, protecting us from unexpected regressions.

- Psychological safety: a work environment where “breaking” something in a test or staging environment is not a crime, but part of the learning and cleaning process.

- Continuous usage verification: how many features were implemented at the request of a client who is no longer one today? How many procedures are used by no one? It is fundamental to ask these questions and act accordingly.

- Facing the fear of “what if it’s needed one day?”: this is the most common excuse for not deleting. Spoiler: that day will almost never come. And even if it did, requirements will have changed to such an extent that rewriting the code from scratch will still be the best option, rather than adapting an old and forgotten solution. Code written for a “future implementation” is a mortgage on the future that is rarely redeemed.

The next step is to simplify complex logic and minimize dependencies. There are virtuous cases of software designed to have zero or very few dependencies, precisely to facilitate distribution and maintenance.

Every self-respecting software project should dedicate time to eliminating and cleaning up, like a sacred ritual. Every line of code is a weight, a responsibility we carry. Every line we add is a line we will have to maintain, test, and debug.

It’s not a drama to delete. With versioning systems like Git, we can always recover what has been removed. But the truth is that, nine times out of ten, that code was just dead weight.

True Mastery Is Simplicity

It’s easy to add. Everyone is good at adding. But removing? That’s where the real game is played.

The mastery of a senior developer is measured not so much by how much code they can write, but by how much code they can eliminate while preserving essential functionalities.

What holds us back is the fear of “I won’t remove it because maybe it will be needed tomorrow”. But that “tomorrow” almost never comes. As the YAGNI principle (You Aren’t Gonna Need It) states: if you don’t need it now, don’t implement it.

The true value lies not in adding, but in distilling the essential, eliminating the noise, and building something that truly works. This is the courage to remove. And this is what differentiates an enlightened programmer from someone who doesn’t see past their own weekend.