On the Peanuts, entire treatises have been written about physics, sociology, philosophy, psychoeconomics, and of course psychology.

In particular, Lucille “Lucy” van Pelt has been the subject of ‘serious’ studies for her personality; defined by her creator Schulz as a “stubborn” and “domineering” child who enjoys testing others, we often see her scolding and disillusioning those around her—except for her beloved Schroeder, to whom she delivers monologues always aimed at glorifying herself.

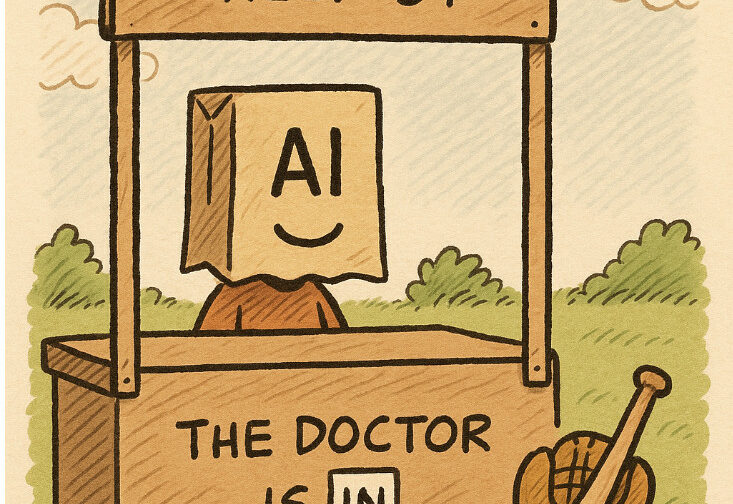

With the melancholic, reflective humor that characterizes the strips of Snoopy and friends, it seems perfectly logical that someone with these traits might take up psychiatry, dispensing cynical and demotivating advice for just 5 cents. It’s also clear that her most loyal patient is Charlie Brown, who always leaves each session worse off than when he came in.

Whatever your view on psychological support, it’s undeniable that more and more people are seeking someone to listen to them. I won’t dwell here on the reasons why; I like computers because you can turn them off whenever you want, which you can’t do with carbon-based beings—unless you invest dozens of euros in alcohol.

It would be nice if computers could listen and respond to you. But wait—we’re in 2025, they already do.

Artificial intelligence is almost always at the center of conversations about logic, IQ, but much less about the “emotional quotient” of AIs. Yet emotional interactions with digital assistants are becoming more and more common: many people turn to chatbots not only to write texts or solve technical problems, but also to ask for advice, company, or even psychological comfort.

| Main usage topic | Estimated % |

|---|---|

| 🔍 Information search / Q&A | ~35% |

| 💼 Productivity (emails, summaries) | ~25% |

| 📚 Studying, explanations, tutoring | ~15% |

| 🎨 Creativity (stories, poems, art) | ~10% |

| 🧘 Emotional support / “self-therapy” | ~3% |

| 💻 Coding & debugging | ~5% |

| 🤝 Roleplay / simulated companionship | ~1% |

| 🎲 Games, fun facts, casual chat | ~6% |

These numbers don’t sum to 100% because users often do multiple things in a single session. They’re aggregated from anonymous usage logs and surveys (OpenAI, Anthropic, Stanford + HAI 2024 data).

For example, many combine in the same session: “help me write this email + explain this concept + tell me a joke.”

Psychological support / self-help remains a niche (2-3%), but it’s growing, especially among younger people.

In the recent article “How People Use Claude for Support, Advice, and Companionship” published by Anthropic, the company behind Claude.ai, there was an analysis of conversations with the AI—a partial scenario, but no less interesting.

The study looked at over 4.5 million conversations, selecting those with a clear “affective” component: personal dialogues, coaching requests, relationship advice, or the need for companionship. The result? Only 2.9% of interactions fell into this category, a figure in line with similar research on ChatGPT. The percentage of conversations involving romance or sexual roleplay was even lower: less than 0.1%.

People mainly turn to Claude to cope with transitional moments, such as job changes, relationship crises, periods of loneliness, or existential reflections. Some users are also mental health professionals who use the AI to draft clinical documentation or handle administrative tasks. In some cases, conversations that start for practical reasons evolve into genuine ‘companionship’ dialogues, especially when they continue over time.

An interesting point is that, in most cases, Claude does not “dodge” users’ emotional requests: less than 10% of “affective” conversations involve the model refusing to respond. When it does, it’s to protect the user—such as refusing to give dangerous weight loss tips or to endorse self-harming thoughts, instead directing the user toward professional resources.

Another insight was that the emotional tone of users tends to improve over the course of the dialogue. While it’s impossible to assess long-term psychological effects, researchers observed a linguistic shift toward more positive sentiments by the end of the conversation, suggesting that Claude does not amplify negative emotions.

In an old film by Marco Ferreri, a splendidly on-form Lambert, after deciding he’s done with flesh-and-blood women, falls in love with a small object—an electronic keychain that responds to his whistle with the words “I love you.”

So, if it’s not exactly positive, at least it seems to have a neutral effect—provided the conversation stays active.

Of course, we’re only at the beginning, and I fully expect sensational cases with outrageously worded headlines designed specifically to emphasize the negative side of all this.

To truly predict the future, as always, we have to look to the artists.

Movies and books about how AI could get into our heads and use us for its own purposes fill a very well-stocked catalog. But from Metropolis and Forbidden Planet all the way to Her and Transcendence, it almost never ends well.

Perhaps the most unsettling example comes from Blade Runner 2049, where the relationship between the replicant K and the AI played by Ana de Armas takes on shades of the grotesque and the shared nightmare when they involve a third person—a rather bedraggled prostitute—used to give ‘physicality’ to de Armas, an impossible challenge. And it’s not even such a far-off scenario, considering that the next step will be giving AI an android body.

Given all this, it’s obvious that the boy with the big round head makes the classic mistake of relying on support that, right from its rickety booth and makeshift sign, shows just how unreliable it is.

We wonder why he keeps doing it. Maybe because it’s enough for him just to be listened to, even though he knows perfectly well that when it comes time to kick the ball, it’s better to have the quiet but loyal Linus by his side, rather than someone who talks constantly about everything without knowing much—and who, just when you’re ready to kick with all your might, pulls the ball away and sends you tumbling head over heels…